Rwanda opens first public coding school

Coding,CNBC, Coding School,All posts by antmilner

2019-02-28

Rwanda opens first public coding school - CNBC AfricaHome Videos Rwanda opens first public coding schoolRecommended for youLatest PostsThis website uses cookies to improve your experience. We'll assume you're ok with this, but you can opt-out if you wish.

Coding drops quantum computing error rate by order of magnitude

Quantum, Coding,All posts by antmilner

2019-02-28

Errors in quantum computing have limited the potential of the emerging technology. Now, however, researchers at Australia’s University of Sydney have demonstrated a new code to catch these bugs.

The promised power of quantum computing lies in the fundamental nature of quantum systems that exist as a mix, or superposition, of all possible states.

A traditional computer processes a series of "bits" that can be either 1 or 0 (or, on or off). The quantum equivalent, called a "qubit", can exist as both 1 and 0 simultaneously, and can be "solved" together.

One outcome of this is an exponential growth in computing power. A traditional computer central processing unit is built on 64-bit architecture. The equivalent-size quantum unit would be capable of representing 18 million trillion states, or calculations, all at the same time.

The challenge with realising the exponential growth in qubit-powered computing is that the quantum states are fragile and prone to collapsing or producing errors when exposed to the electrical ‘noise’ from the world around them. If these bugs could be caught by software it would make the underlying hardware much more useful for calculations.

“This is really the first time that the promised benefit for quantum logic gates from theory has been realised in an actual quantum machine,” says Robin Harper, lead author of a new paper published in the journal, Physical Review Letters.

Harper and his colleague Steven Flammia implemented their code on one of tech giant IBM’s quantum computers, made available through the corporation’s IBM Q initiative. The result was a reduction in the error rate by an order of magnitude.

The test was performed on quantum logic gates, the building blocks of any quantum computer, and the equivalent of classical logic gates.

“Current devices tend to be too small, with limited interconnectivity between qubits and are too ‘noisy’ to allow meaningful computations,” Harper says.

“However, they are sufficient to act as test beds for proof of principle concepts, such as detecting and potentially correcting errors using quantum codes.”

Everyday devices have electronics which can operate for decades without error, but a quantum system can experience an error just fractions of a second after booting up.

Improving that length of time is a critical step in the quest to scale up from simple logic gates to larger computing systems.

The team’s code was able to drop error rates on IBM’s systems from 5.8% to 0.60%.

“One way to look at this is through the concept of entropy,” explains Flammia.

“All systems tend to disorder. In conventional computers, systems are refreshed easily, effectively dumping the entropy out of the system, allowing ordered computation.

“In quantum systems, effective reset methods to combat entropy are much harder to engineer. The codes we use are one way to dump this entropy from the system.”

Coding a Better Future

Coding, Ethics, Computer Science,All posts by antmilner

2019-02-28

Embedded EthiCS, a collaborative initiative between the Computer Science and Philosophy Departments, now offers a dozen courses, tripling its size since when it began spring 2017. The initiative, which offers interdisciplinary courses that address the ethical issues surrounding technology and computer science, also plans to expand to other disciplines.

We strongly applaud this exciting, innovative initiative from the Computer Science and Philosophy Departments. The creation of Embedded EthiCS affirms the two departments’ understanding that examining the ethics at play in a novel field like computer science is an essential part of developing the field responsibly. We are heartened by the program’s expansion, and further encourage the integration of this interdisciplinary approach in other academic departments so that ethics becomes a valued component of every discipline.

An understanding of ethical issues arising from the rapid growth of technology in our society is not only useful, but also morally vital. Issues of data collection and privacy of information — to name just a few concerns — have posed challenges in the field of computer science, and it is of the utmost importance that students concentrating in the field think seriously about them. To that end, the Embedded EthiCS program is not only creating new ethics-based courses, but also aiming at integrating ethical questions into pre-existing courses across Computer Science. By this process, rather than learning just the most efficient coding techniques, students will also have to confront the implications of the systems they create on the world around them.

At a place like Harvard, where students in all disciplines will go on to shape their fields, this type of interdisciplinary initiative should not be restricted to the Computer Science department. In light of ethical challenges emerging in other STEM fields like genetics, we feel that this initiative should expand to other schools across the University such as the School for Engineering and Applied Sciences. Encouragingly, the program already plans to expand to the Medical School. Even within the College, we hope that the program grows, so that all students, regardless of concentration, will be able to take ethical reasoning classes designed to engage directly with issues related to their concentration.

Even beyond Harvard, we encourage this type of interdisciplinary approach to learning at colleges and universities across the U.S. in all kinds of different contexts. By making the materials for Embedded EthiCS courses available online, the program has made concrete steps to work towards just such a goal. We commend this move, and hope these academic initiatives across Harvard and academia more broadly will encourage students to think more deeply about how they can use their talents not just to succeed in their industry of choice, but to build a better world.

This staff editorial solely represents the majority view of The Crimson Editorial Board. It is the product of discussions at regular Editorial Board meetings. In order to ensure the impartiality of our journalism, Crimson editors who choose to opine and vote at these meetings are not involved in the reporting of articles on similar topics.

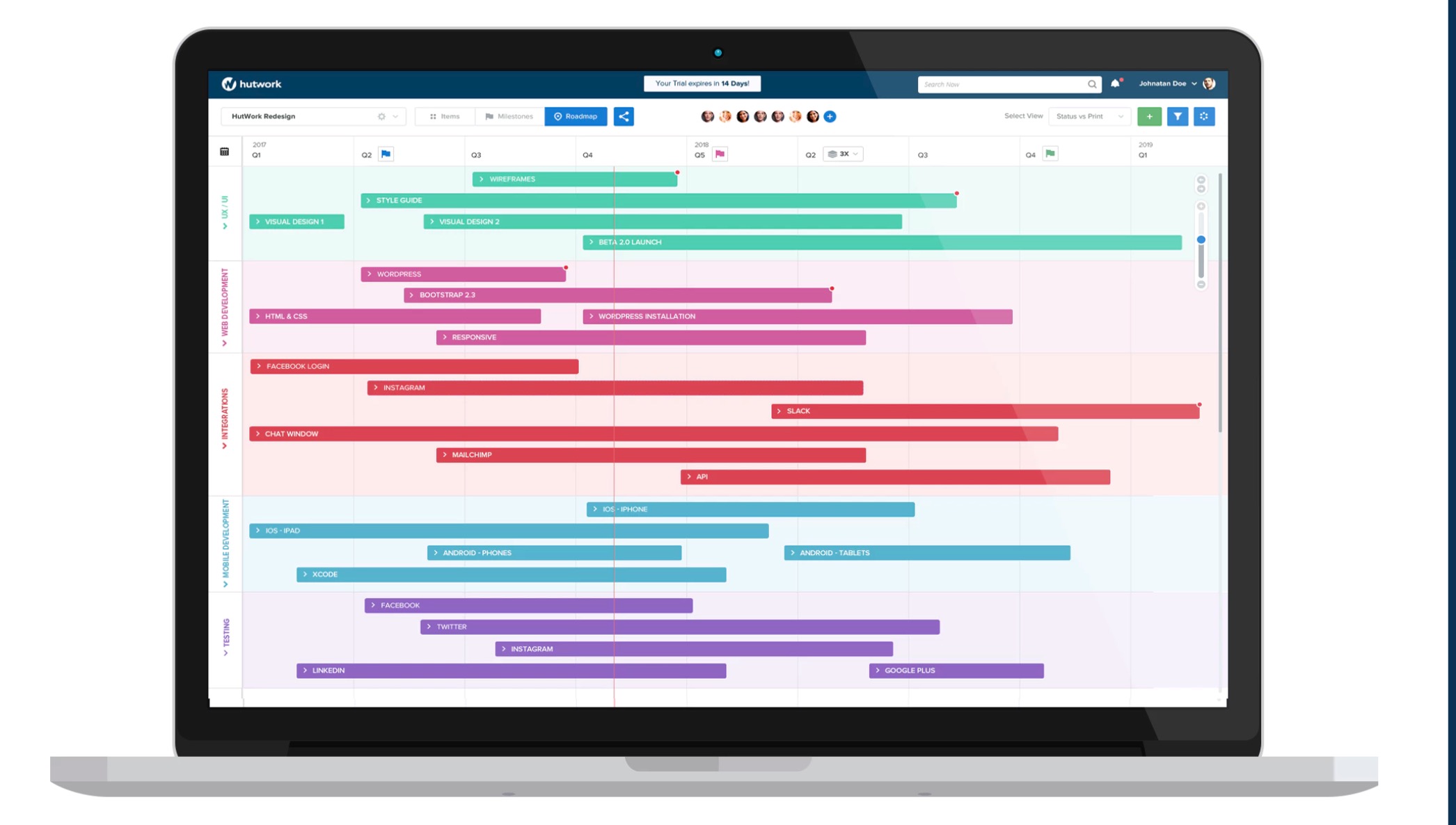

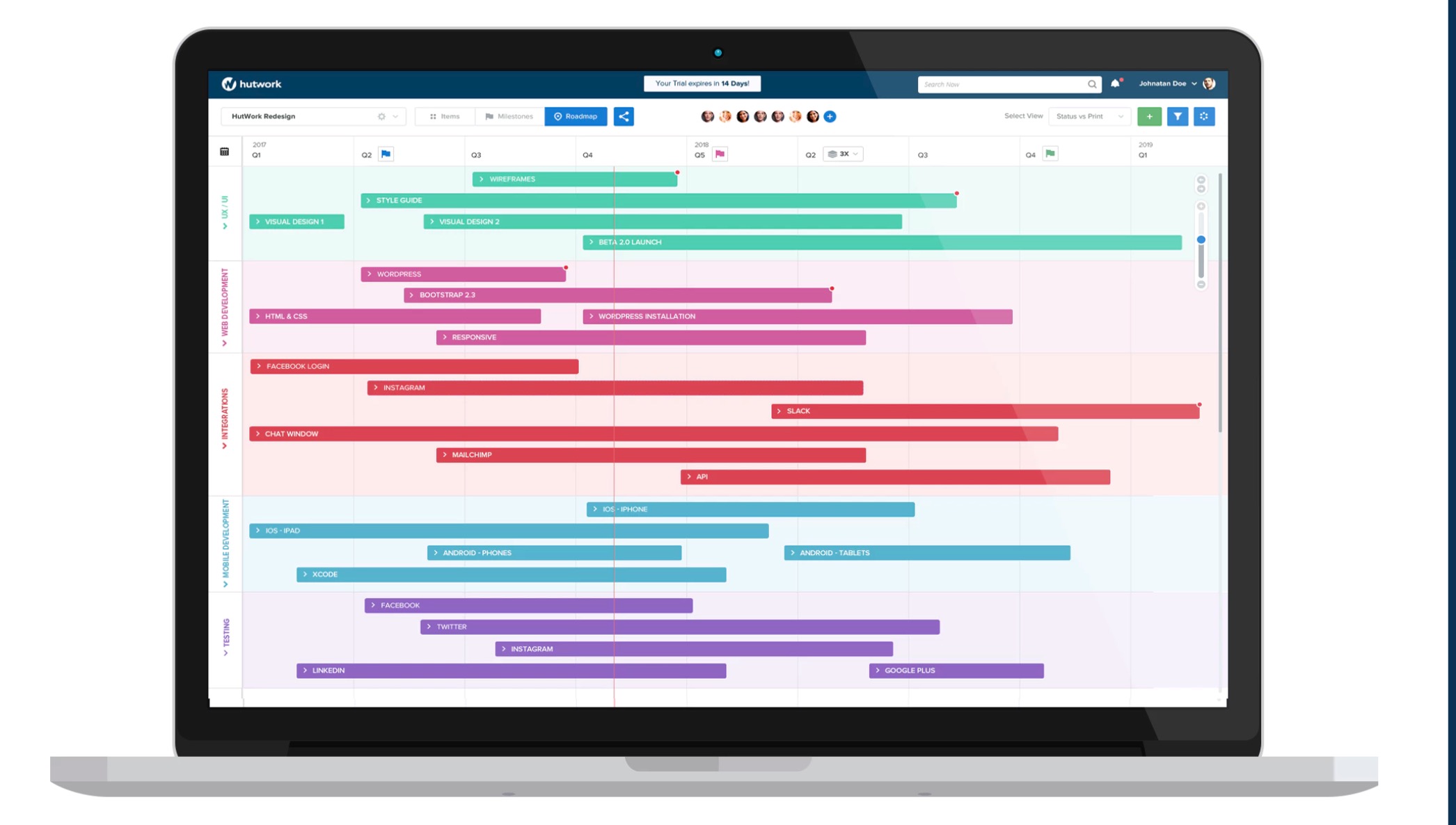

The Cloud Is Just Someone Else's Computer

Cloud, Servers, CodingAll posts by antmilner

2019-02-28

When we started Discourse in 2013, our server requirements were high:

- 1GB RAM

- modern, fast dual core CPU

- speedy solid state drive with 20+ GB

I'm not talking about a cheapo shared cpanel server, either, I mean a dedicated virtual private server with those specifications.

We were OK with that, because we were building in Ruby for the next decade of the Internet. I predicted early on that the cost of renting a suitable VPS would drop to $5 per month, and courtesy of Digital Ocean that indeed happened in January 2018.

The cloud got cheaper, and faster. Not really a surprise, since the price of hardware trends to zero over time. But it's still the cloud, and that means it isn't exactly cheap. It is, after all, someone else's computer that you pay for the privilege of renting.

But wait … what if you could put your own computer "in the cloud"?

Wouldn't that be the best of both worlds? Reliable connectivity, plus a nice low monthly price for extremely fast hardware? If this sounds crazy, it shouldn't – Mac users have been doing this for years now.

A Gentle Introduction to Learning Curves for Diagnosing Machine Learning Model Performance

Machine Learning, AI, ML, Model PerformaceAll posts by antmilner

2019-02-28

A Gentle Introduction to Learning Curves for Diagnosing Machine Learning Model Performance

by Jason Brownlee on February 27, 2019 in Better Deep Learning

Tweet Share Share

A learning curve is a plot of model learning performance over experience or time.

Learning curves are a widely used diagnostic tool in machine learning for algorithms that learn from a training dataset incrementally. The model can be evaluated on the training dataset and on a hold out validation dataset after each update during training and plots of the measured performance can created to show learning curves.

Reviewing learning curves of models during training can be used to diagnose problems with learning, such as an underfit or overfit model, as well as whether the training and validation datasets are suitably representative.

In this post, you will discover learning curves and how they can be used to diagnose the learning and generalization behavior of machine learning models, with example plots showing common learning problems.

After reading this post, you will know:

- Learning curves are plots that show changes in learning performance over time in terms of experience.

- Learning curves of model performance on the train and validation datasets can be used to diagnose an underfit, overfit, or well-fit model.

- Learning curves of model performance can be used to diagnose whether the train or validation datasets are not relatively representative of the problem domain.

Let’s get started.

Overview

This tutorial is divided into three parts; they are:

- Learning Curves

- Diagnosing Model Behavior

- Diagnosing Unrepresentative Datasets

Learning Curves in Machine Learning

Generally, a learning curve is a plot that shows time or experience on the x-axis and learning or improvement on the y-axis.

Learning curves (LCs) are deemed effective tools for monitoring the performance of workers exposed to a new task. LCs provide a mathematical representation of the learning process that takes place as task repetition occurs.

— Learning curve models and applications: Literature review and research directions, 2011.

For example, if you were learning a musical instrument, your skill on the instrument could be evaluated and assigned a numerical score each week for one year. A plot of the scores over the 52 weeks is a learning curve and would show how your learning of the instrument has changed over time.

- Learning Curve: Line plot of learning (y-axis) over experience (x-axis).

Learning curves are widely used in machine learning for algorithms that learn (optimize their internal parameters) incrementally over time, such as deep learning neural networks.

The metric used to evaluate learning could be maximizing, meaning that better scores (larger numbers) indicate more learning. An example would be classification accuracy.

It is more common to use a score that is minimizing, such as loss or error whereby better scores (smaller numbers) indicate more learning and a value of 0.0 indicates that the training dataset was learned perfectly and no mistakes were made.

During the training of a machine learning model, the current state of the model at each step of the training algorithm can be evaluated. It can be evaluated on the training dataset to give an idea of how well the model is “learning.” It can also be evaluated on a hold-out validation dataset that is not part of the training dataset. Evaluation on the validation dataset gives an idea of how well the model is “generalizing.”

- Train Learning Curve: Learning curve calculated from the training dataset that gives an idea of how well the model is learning.

- Validation Learning Curve: Learning curve calculated from a hold-out validation dataset that gives an idea of how well the model is generalizing.

It is common to create dual learning curves for a machine learning model during training on both the training and validation datasets.

In some cases, it is also common to create learning curves for multiple metrics, such as in the case of classification predictive modeling problems, where the model may be optimized according to cross-entropy loss and model performance is evaluated using classification accuracy. In this case, two plots are created, one for the learning curves of each metric, and each plot can show two learning curves, one for each of the train and validation datasets.

- Optimization Learning Curves: Learning curves calculated on the metric by which the parameters of the model are being optimized, e.g. loss.

- Performance Learning Curves: Learning curves calculated on the metric by which the model will be evaluated and selected, e.g. accuracy.

Now that we are familiar with the use of learning curves in machine learning, let’s look at some common shapes observed in learning curve plots.

A Gentle Introduction to Learning Curves for Diagnosing Machine Learning Model Performance

by Jason Brownlee on February 27, 2019 in Better Deep Learning

Tweet Share Share

A learning curve is a plot of model learning performance over experience or time.

Learning curves are a widely used diagnostic tool in machine learning for algorithms that learn from a training dataset incrementally. The model can be evaluated on the training dataset and on a hold out validation dataset after each update during training and plots of the measured performance can created to show learning curves.

Reviewing learning curves of models during training can be used to diagnose problems with learning, such as an underfit or overfit model, as well as whether the training and validation datasets are suitably representative.

In this post, you will discover learning curves and how they can be used to diagnose the learning and generalization behavior of machine learning models, with example plots showing common learning problems.

After reading this post, you will know:

- Learning curves are plots that show changes in learning performance over time in terms of experience.

- Learning curves of model performance on the train and validation datasets can be used to diagnose an underfit, overfit, or well-fit model.

- Learning curves of model performance can be used to diagnose whether the train or validation datasets are not relatively representative of the problem domain.

Let’s get started.

A Gentle Introduction to Learning Curves for Diagnosing Deep Learning Model PerformancePhoto by Mike Sutherland, some rights reserved.

Overview

This tutorial is divided into three parts; they are:

- Learning Curves

- Diagnosing Model Behavior

- Diagnosing Unrepresentative Datasets

Learning Curves in Machine Learning

Generally, a learning curve is a plot that shows time or experience on the x-axis and learning or improvement on the y-axis.

Learning curves (LCs) are deemed effective tools for monitoring the performance of workers exposed to a new task. LCs provide a mathematical representation of the learning process that takes place as task repetition occurs.

— Learning curve models and applications: Literature review and research directions, 2011.

For example, if you were learning a musical instrument, your skill on the instrument could be evaluated and assigned a numerical score each week for one year. A plot of the scores over the 52 weeks is a learning curve and would show how your learning of the instrument has changed over time.

- Learning Curve: Line plot of learning (y-axis) over experience (x-axis).

Learning curves are widely used in machine learning for algorithms that learn (optimize their internal parameters) incrementally over time, such as deep learning neural networks.

The metric used to evaluate learning could be maximizing, meaning that better scores (larger numbers) indicate more learning. An example would be classification accuracy.

It is more common to use a score that is minimizing, such as loss or error whereby better scores (smaller numbers) indicate more learning and a value of 0.0 indicates that the training dataset was learned perfectly and no mistakes were made.

During the training of a machine learning model, the current state of the model at each step of the training algorithm can be evaluated. It can be evaluated on the training dataset to give an idea of how well the model is “learning.” It can also be evaluated on a hold-out validation dataset that is not part of the training dataset. Evaluation on the validation dataset gives an idea of how well the model is “generalizing.”

- Train Learning Curve: Learning curve calculated from the training dataset that gives an idea of how well the model is learning.

- Validation Learning Curve: Learning curve calculated from a hold-out validation dataset that gives an idea of how well the model is generalizing.

It is common to create dual learning curves for a machine learning model during training on both the training and validation datasets.

In some cases, it is also common to create learning curves for multiple metrics, such as in the case of classification predictive modeling problems, where the model may be optimized according to cross-entropy loss and model performance is evaluated using classification accuracy. In this case, two plots are created, one for the learning curves of each metric, and each plot can show two learning curves, one for each of the train and validation datasets.

- Optimization Learning Curves: Learning curves calculated on the metric by which the parameters of the model are being optimized, e.g. loss.

- Performance Learning Curves: Learning curves calculated on the metric by which the model will be evaluated and selected, e.g. accuracy.

Now that we are familiar with the use of learning curves in machine learning, let’s look at some common shapes observed in learning curve plots.

Want Better Results with Deep Learning?

Take my free 7-day email crash course now (with sample code).

Click to sign-up and also get a free PDF Ebook version of the course.

Download Your FREE Mini-Course

Diagnosing Model Behavior

The shape and dynamics of a learning curve can be used to diagnose the behavior of a machine learning model and in turn perhaps suggest at the type of configuration changes that may be made to improve learning and/or performance.

There are three common dynamics that you are likely to observe in learning curves; they are:

- Underfit.

- Overfit.

- Good Fit.

We will take a closer look at each with examples. The examples will assume that we are looking at a minimizing metric, meaning that smaller relative scores on the y-axis indicate more or better learning.

Underfit Learning Curves

Underfitting refers to a model that cannot learn the training dataset.

Underfitting occurs when the model is not able to obtain a sufficiently low error value on the training set.

— Page 111, Deep Learning, 2016.

An underfit model can be identified from the learning curve of the training loss only.

It may show a flat line or noisy values of relatively high loss, indicating that the model was unable to learn the training dataset at all.

An example of this is provided below and is common when the model does not have a suitable capacity for the complexity of the dataset.

Example of Training Learning Curve Showing An Underfit Model That Does Not Have Sufficient Capacity

An underfit model may also be identified by a training loss that is decreasing and continues to decrease at the end of the plot.

This indicates that the model is capable of further learning and possible further improvements and that the training process was halted prematurely.

Example of Training Learning Curve Showing an Underfit Model That Requires Further Training

A plot of learning curves shows overfitting if:

- The training loss remains flat regardless of training.

- The training loss continues to decrease until the end of training.

Overfit Learning Curves

Overfitting refers to a model that has learned the training dataset too well, including the statistical noise or random fluctuations in the training dataset.

… fitting a more flexible model requires estimating a greater number of parameters. These more complex models can lead to a phenomenon known as overfitting the data, which essentially means they follow the errors, or noise, too closely.

— Page 22, An Introduction to Statistical Learning: with Applications in R, 2013.

The problem with overfitting, is that the more specialized the model becomes to training data, the less well it is able to generalize to new data, resulting in an increase in generalization error. This increase in generalization error can be measured by the performance of the model on the validation dataset.

This is an example of overfitting the data, […]. It is an undesirable situation because the fit obtained will not yield accurate estimates of the response on new observations that were not part of the original training data set.

— Page 24, An Introduction to Statistical Learning: with Applications in R, 2013.

This often occurs if the model has more capacity than is required for the problem, and, in turn, too much flexibility. It can also occur if the model is trained for too long.

A plot of learning curves shows overfitting if:

- The plot of training loss continues to decrease with experience.

- The plot of validation loss decreases to a point and begins increasing again.

The inflection point in validation loss may be the point at which training could be halted as experience after that point shows the dynamics of overfitting.

The example plot below demonstrates a case of overfitting.

Example of Train and Validation Learning Curves Showing an Overfit Model

Good Fit Learning Curves

A good fit is the goal of the learning algorithm and exists between an overfit and underfit model.

A good fit is identified by a training and validation loss that decreases to a point of stability with a minimal gap between the two final loss values.

The loss of the model will almost always be lower on the training dataset than the validation dataset. This means that we should expect some gap between the train and validation loss learning curves. This gap is referred to as the “generalization gap.”

A plot of learning curves shows a good fit if:

- The plot of training loss decreases to a point of stability.

- The plot of validation loss decreases to a point of stability and has a small gap with the training loss.

Continued training of a good fit will likely lead to an overfit.

The example plot below demonstrates a case of a good fit.

Example of Train and Validation Learning Curves Showing a Good Fit

A Gentle Introduction to Learning Curves for Diagnosing Machine Learning Model Performance

Machine Learning, AI, ML, Model PerformaceAll posts by antmilner

2019-02-28

A Gentle Introduction to Learning Curves for Diagnosing Machine Learning Model Performance

by Jason Brownlee on February 27, 2019 in Better Deep Learning

Tweet Share Share

A learning curve is a plot of model learning performance over experience or time.

Learning curves are a widely used diagnostic tool in machine learning for algorithms that learn from a training dataset incrementally. The model can be evaluated on the training dataset and on a hold out validation dataset after each update during training and plots of the measured performance can created to show learning curves.

Reviewing learning curves of models during training can be used to diagnose problems with learning, such as an underfit or overfit model, as well as whether the training and validation datasets are suitably representative.

In this post, you will discover learning curves and how they can be used to diagnose the learning and generalization behavior of machine learning models, with example plots showing common learning problems.

After reading this post, you will know:

- Learning curves are plots that show changes in learning performance over time in terms of experience.

- Learning curves of model performance on the train and validation datasets can be used to diagnose an underfit, overfit, or well-fit model.

- Learning curves of model performance can be used to diagnose whether the train or validation datasets are not relatively representative of the problem domain.

Let’s get started.

Overview

This tutorial is divided into three parts; they are:

- Learning Curves

- Diagnosing Model Behavior

- Diagnosing Unrepresentative Datasets

Learning Curves in Machine Learning

Generally, a learning curve is a plot that shows time or experience on the x-axis and learning or improvement on the y-axis.

Learning curves (LCs) are deemed effective tools for monitoring the performance of workers exposed to a new task. LCs provide a mathematical representation of the learning process that takes place as task repetition occurs.

— Learning curve models and applications: Literature review and research directions, 2011.

For example, if you were learning a musical instrument, your skill on the instrument could be evaluated and assigned a numerical score each week for one year. A plot of the scores over the 52 weeks is a learning curve and would show how your learning of the instrument has changed over time.

- Learning Curve: Line plot of learning (y-axis) over experience (x-axis).

Learning curves are widely used in machine learning for algorithms that learn (optimize their internal parameters) incrementally over time, such as deep learning neural networks.

The metric used to evaluate learning could be maximizing, meaning that better scores (larger numbers) indicate more learning. An example would be classification accuracy.

It is more common to use a score that is minimizing, such as loss or error whereby better scores (smaller numbers) indicate more learning and a value of 0.0 indicates that the training dataset was learned perfectly and no mistakes were made.

During the training of a machine learning model, the current state of the model at each step of the training algorithm can be evaluated. It can be evaluated on the training dataset to give an idea of how well the model is “learning.” It can also be evaluated on a hold-out validation dataset that is not part of the training dataset. Evaluation on the validation dataset gives an idea of how well the model is “generalizing.”

- Train Learning Curve: Learning curve calculated from the training dataset that gives an idea of how well the model is learning.

- Validation Learning Curve: Learning curve calculated from a hold-out validation dataset that gives an idea of how well the model is generalizing.

It is common to create dual learning curves for a machine learning model during training on both the training and validation datasets.

In some cases, it is also common to create learning curves for multiple metrics, such as in the case of classification predictive modeling problems, where the model may be optimized according to cross-entropy loss and model performance is evaluated using classification accuracy. In this case, two plots are created, one for the learning curves of each metric, and each plot can show two learning curves, one for each of the train and validation datasets.

- Optimization Learning Curves: Learning curves calculated on the metric by which the parameters of the model are being optimized, e.g. loss.

- Performance Learning Curves: Learning curves calculated on the metric by which the model will be evaluated and selected, e.g. accuracy.

Now that we are familiar with the use of learning curves in machine learning, let’s look at some common shapes observed in learning curve plots.

A Gentle Introduction to Learning Curves for Diagnosing Machine Learning Model Performance

by Jason Brownlee on February 27, 2019 in Better Deep Learning

Tweet Share Share

A learning curve is a plot of model learning performance over experience or time.

Learning curves are a widely used diagnostic tool in machine learning for algorithms that learn from a training dataset incrementally. The model can be evaluated on the training dataset and on a hold out validation dataset after each update during training and plots of the measured performance can created to show learning curves.

Reviewing learning curves of models during training can be used to diagnose problems with learning, such as an underfit or overfit model, as well as whether the training and validation datasets are suitably representative.

In this post, you will discover learning curves and how they can be used to diagnose the learning and generalization behavior of machine learning models, with example plots showing common learning problems.

After reading this post, you will know:

- Learning curves are plots that show changes in learning performance over time in terms of experience.

- Learning curves of model performance on the train and validation datasets can be used to diagnose an underfit, overfit, or well-fit model.

- Learning curves of model performance can be used to diagnose whether the train or validation datasets are not relatively representative of the problem domain.

Let’s get started.

A Gentle Introduction to Learning Curves for Diagnosing Deep Learning Model PerformancePhoto by Mike Sutherland, some rights reserved.

Overview

This tutorial is divided into three parts; they are:

- Learning Curves

- Diagnosing Model Behavior

- Diagnosing Unrepresentative Datasets

Learning Curves in Machine Learning

Generally, a learning curve is a plot that shows time or experience on the x-axis and learning or improvement on the y-axis.

Learning curves (LCs) are deemed effective tools for monitoring the performance of workers exposed to a new task. LCs provide a mathematical representation of the learning process that takes place as task repetition occurs.

— Learning curve models and applications: Literature review and research directions, 2011.

For example, if you were learning a musical instrument, your skill on the instrument could be evaluated and assigned a numerical score each week for one year. A plot of the scores over the 52 weeks is a learning curve and would show how your learning of the instrument has changed over time.

- Learning Curve: Line plot of learning (y-axis) over experience (x-axis).

Learning curves are widely used in machine learning for algorithms that learn (optimize their internal parameters) incrementally over time, such as deep learning neural networks.

The metric used to evaluate learning could be maximizing, meaning that better scores (larger numbers) indicate more learning. An example would be classification accuracy.

It is more common to use a score that is minimizing, such as loss or error whereby better scores (smaller numbers) indicate more learning and a value of 0.0 indicates that the training dataset was learned perfectly and no mistakes were made.

During the training of a machine learning model, the current state of the model at each step of the training algorithm can be evaluated. It can be evaluated on the training dataset to give an idea of how well the model is “learning.” It can also be evaluated on a hold-out validation dataset that is not part of the training dataset. Evaluation on the validation dataset gives an idea of how well the model is “generalizing.”

- Train Learning Curve: Learning curve calculated from the training dataset that gives an idea of how well the model is learning.

- Validation Learning Curve: Learning curve calculated from a hold-out validation dataset that gives an idea of how well the model is generalizing.

It is common to create dual learning curves for a machine learning model during training on both the training and validation datasets.

In some cases, it is also common to create learning curves for multiple metrics, such as in the case of classification predictive modeling problems, where the model may be optimized according to cross-entropy loss and model performance is evaluated using classification accuracy. In this case, two plots are created, one for the learning curves of each metric, and each plot can show two learning curves, one for each of the train and validation datasets.

- Optimization Learning Curves: Learning curves calculated on the metric by which the parameters of the model are being optimized, e.g. loss.

- Performance Learning Curves: Learning curves calculated on the metric by which the model will be evaluated and selected, e.g. accuracy.

Now that we are familiar with the use of learning curves in machine learning, let’s look at some common shapes observed in learning curve plots.

Want Better Results with Deep Learning?

Take my free 7-day email crash course now (with sample code).

Click to sign-up and also get a free PDF Ebook version of the course.

Download Your FREE Mini-Course

Diagnosing Model Behavior

The shape and dynamics of a learning curve can be used to diagnose the behavior of a machine learning model and in turn perhaps suggest at the type of configuration changes that may be made to improve learning and/or performance.

There are three common dynamics that you are likely to observe in learning curves; they are:

- Underfit.

- Overfit.

- Good Fit.

We will take a closer look at each with examples. The examples will assume that we are looking at a minimizing metric, meaning that smaller relative scores on the y-axis indicate more or better learning.

Underfit Learning Curves

Underfitting refers to a model that cannot learn the training dataset.

Underfitting occurs when the model is not able to obtain a sufficiently low error value on the training set.

— Page 111, Deep Learning, 2016.

An underfit model can be identified from the learning curve of the training loss only.

It may show a flat line or noisy values of relatively high loss, indicating that the model was unable to learn the training dataset at all.

An example of this is provided below and is common when the model does not have a suitable capacity for the complexity of the dataset.

Example of Training Learning Curve Showing An Underfit Model That Does Not Have Sufficient Capacity

An underfit model may also be identified by a training loss that is decreasing and continues to decrease at the end of the plot.

This indicates that the model is capable of further learning and possible further improvements and that the training process was halted prematurely.

Example of Training Learning Curve Showing an Underfit Model That Requires Further Training

A plot of learning curves shows overfitting if:

- The training loss remains flat regardless of training.

- The training loss continues to decrease until the end of training.

Overfit Learning Curves

Overfitting refers to a model that has learned the training dataset too well, including the statistical noise or random fluctuations in the training dataset.

… fitting a more flexible model requires estimating a greater number of parameters. These more complex models can lead to a phenomenon known as overfitting the data, which essentially means they follow the errors, or noise, too closely.

— Page 22, An Introduction to Statistical Learning: with Applications in R, 2013.

The problem with overfitting, is that the more specialized the model becomes to training data, the less well it is able to generalize to new data, resulting in an increase in generalization error. This increase in generalization error can be measured by the performance of the model on the validation dataset.

This is an example of overfitting the data, […]. It is an undesirable situation because the fit obtained will not yield accurate estimates of the response on new observations that were not part of the original training data set.

— Page 24, An Introduction to Statistical Learning: with Applications in R, 2013.

This often occurs if the model has more capacity than is required for the problem, and, in turn, too much flexibility. It can also occur if the model is trained for too long.

A plot of learning curves shows overfitting if:

- The plot of training loss continues to decrease with experience.

- The plot of validation loss decreases to a point and begins increasing again.

The inflection point in validation loss may be the point at which training could be halted as experience after that point shows the dynamics of overfitting.

The example plot below demonstrates a case of overfitting.

Example of Train and Validation Learning Curves Showing an Overfit Model

Good Fit Learning Curves

A good fit is the goal of the learning algorithm and exists between an overfit and underfit model.

A good fit is identified by a training and validation loss that decreases to a point of stability with a minimal gap between the two final loss values.

The loss of the model will almost always be lower on the training dataset than the validation dataset. This means that we should expect some gap between the train and validation loss learning curves. This gap is referred to as the “generalization gap.”

A plot of learning curves shows a good fit if:

- The plot of training loss decreases to a point of stability.

- The plot of validation loss decreases to a point of stability and has a small gap with the training loss.

Continued training of a good fit will likely lead to an overfit.

The example plot below demonstrates a case of a good fit.

Example of Train and Validation Learning Curves Showing a Good Fit

The Cloud Is Just Someone Else's Computer

Cloud, Servers, CodingAll posts by antmilner

2019-02-28

When we started Discourse in 2013, our server requirements were high:

- 1GB RAM

- modern, fast dual core CPU

- speedy solid state drive with 20+ GB

I'm not talking about a cheapo shared cpanel server, either, I mean a dedicated virtual private server with those specifications.

We were OK with that, because we were building in Ruby for the next decade of the Internet. I predicted early on that the cost of renting a suitable VPS would drop to $5 per month, and courtesy of Digital Ocean that indeed happened in January 2018.

The cloud got cheaper, and faster. Not really a surprise, since the price of hardware trends to zero over time. But it's still the cloud, and that means it isn't exactly cheap. It is, after all, someone else's computer that you pay for the privilege of renting.

But wait … what if you could put your own computer "in the cloud"?

Wouldn't that be the best of both worlds? Reliable connectivity, plus a nice low monthly price for extremely fast hardware? If this sounds crazy, it shouldn't – Mac users have been doing this for years now.

Coding a Better Future

Coding, Ethics, Computer Science,All posts by antmilner

2019-02-28

Embedded EthiCS, a collaborative initiative between the Computer Science and Philosophy Departments, now offers a dozen courses, tripling its size since when it began spring 2017. The initiative, which offers interdisciplinary courses that address the ethical issues surrounding technology and computer science, also plans to expand to other disciplines.

We strongly applaud this exciting, innovative initiative from the Computer Science and Philosophy Departments. The creation of Embedded EthiCS affirms the two departments’ understanding that examining the ethics at play in a novel field like computer science is an essential part of developing the field responsibly. We are heartened by the program’s expansion, and further encourage the integration of this interdisciplinary approach in other academic departments so that ethics becomes a valued component of every discipline.

An understanding of ethical issues arising from the rapid growth of technology in our society is not only useful, but also morally vital. Issues of data collection and privacy of information — to name just a few concerns — have posed challenges in the field of computer science, and it is of the utmost importance that students concentrating in the field think seriously about them. To that end, the Embedded EthiCS program is not only creating new ethics-based courses, but also aiming at integrating ethical questions into pre-existing courses across Computer Science. By this process, rather than learning just the most efficient coding techniques, students will also have to confront the implications of the systems they create on the world around them.

At a place like Harvard, where students in all disciplines will go on to shape their fields, this type of interdisciplinary initiative should not be restricted to the Computer Science department. In light of ethical challenges emerging in other STEM fields like genetics, we feel that this initiative should expand to other schools across the University such as the School for Engineering and Applied Sciences. Encouragingly, the program already plans to expand to the Medical School. Even within the College, we hope that the program grows, so that all students, regardless of concentration, will be able to take ethical reasoning classes designed to engage directly with issues related to their concentration.

Even beyond Harvard, we encourage this type of interdisciplinary approach to learning at colleges and universities across the U.S. in all kinds of different contexts. By making the materials for Embedded EthiCS courses available online, the program has made concrete steps to work towards just such a goal. We commend this move, and hope these academic initiatives across Harvard and academia more broadly will encourage students to think more deeply about how they can use their talents not just to succeed in their industry of choice, but to build a better world.

This staff editorial solely represents the majority view of The Crimson Editorial Board. It is the product of discussions at regular Editorial Board meetings. In order to ensure the impartiality of our journalism, Crimson editors who choose to opine and vote at these meetings are not involved in the reporting of articles on similar topics.

Coding drops quantum computing error rate by order of magnitude

Quantum, Coding,All posts by antmilner

2019-02-28

Errors in quantum computing have limited the potential of the emerging technology. Now, however, researchers at Australia’s University of Sydney have demonstrated a new code to catch these bugs.

The promised power of quantum computing lies in the fundamental nature of quantum systems that exist as a mix, or superposition, of all possible states.

A traditional computer processes a series of "bits" that can be either 1 or 0 (or, on or off). The quantum equivalent, called a "qubit", can exist as both 1 and 0 simultaneously, and can be "solved" together.

One outcome of this is an exponential growth in computing power. A traditional computer central processing unit is built on 64-bit architecture. The equivalent-size quantum unit would be capable of representing 18 million trillion states, or calculations, all at the same time.

The challenge with realising the exponential growth in qubit-powered computing is that the quantum states are fragile and prone to collapsing or producing errors when exposed to the electrical ‘noise’ from the world around them. If these bugs could be caught by software it would make the underlying hardware much more useful for calculations.

“This is really the first time that the promised benefit for quantum logic gates from theory has been realised in an actual quantum machine,” says Robin Harper, lead author of a new paper published in the journal, Physical Review Letters.

Harper and his colleague Steven Flammia implemented their code on one of tech giant IBM’s quantum computers, made available through the corporation’s IBM Q initiative. The result was a reduction in the error rate by an order of magnitude.

The test was performed on quantum logic gates, the building blocks of any quantum computer, and the equivalent of classical logic gates.

“Current devices tend to be too small, with limited interconnectivity between qubits and are too ‘noisy’ to allow meaningful computations,” Harper says.

“However, they are sufficient to act as test beds for proof of principle concepts, such as detecting and potentially correcting errors using quantum codes.”

Everyday devices have electronics which can operate for decades without error, but a quantum system can experience an error just fractions of a second after booting up.

Improving that length of time is a critical step in the quest to scale up from simple logic gates to larger computing systems.

The team’s code was able to drop error rates on IBM’s systems from 5.8% to 0.60%.

“One way to look at this is through the concept of entropy,” explains Flammia.

“All systems tend to disorder. In conventional computers, systems are refreshed easily, effectively dumping the entropy out of the system, allowing ordered computation.

“In quantum systems, effective reset methods to combat entropy are much harder to engineer. The codes we use are one way to dump this entropy from the system.”

Rwanda opens first public coding school

Coding,CNBC, Coding School,All posts by antmilner

2019-02-28

Rwanda opens first public coding school - CNBC AfricaHome Videos Rwanda opens first public coding schoolRecommended for youLatest PostsThis website uses cookies to improve your experience. We'll assume you're ok with this, but you can opt-out if you wish.

Rwanda opens first public coding school

Coding,CNBC, Coding School,All posts by antmilner

2019-02-28

Rwanda opens first public coding school - CNBC AfricaHome Videos Rwanda opens first public coding schoolRecommended for youLatest PostsThis website uses cookies to improve your experience. We'll assume you're ok with this, but you can opt-out if you wish.

Coding drops quantum computing error rate by order of magnitude

Quantum, Coding,All posts by antmilner

2019-02-28

Errors in quantum computing have limited the potential of the emerging technology. Now, however, researchers at Australia’s University of Sydney have demonstrated a new code to catch these bugs.

The promised power of quantum computing lies in the fundamental nature of quantum systems that exist as a mix, or superposition, of all possible states.

A traditional computer processes a series of "bits" that can be either 1 or 0 (or, on or off). The quantum equivalent, called a "qubit", can exist as both 1 and 0 simultaneously, and can be "solved" together.

One outcome of this is an exponential growth in computing power. A traditional computer central processing unit is built on 64-bit architecture. The equivalent-size quantum unit would be capable of representing 18 million trillion states, or calculations, all at the same time.

The challenge with realising the exponential growth in qubit-powered computing is that the quantum states are fragile and prone to collapsing or producing errors when exposed to the electrical ‘noise’ from the world around them. If these bugs could be caught by software it would make the underlying hardware much more useful for calculations.

“This is really the first time that the promised benefit for quantum logic gates from theory has been realised in an actual quantum machine,” says Robin Harper, lead author of a new paper published in the journal, Physical Review Letters.

Harper and his colleague Steven Flammia implemented their code on one of tech giant IBM’s quantum computers, made available through the corporation’s IBM Q initiative. The result was a reduction in the error rate by an order of magnitude.

The test was performed on quantum logic gates, the building blocks of any quantum computer, and the equivalent of classical logic gates.

“Current devices tend to be too small, with limited interconnectivity between qubits and are too ‘noisy’ to allow meaningful computations,” Harper says.

“However, they are sufficient to act as test beds for proof of principle concepts, such as detecting and potentially correcting errors using quantum codes.”

Everyday devices have electronics which can operate for decades without error, but a quantum system can experience an error just fractions of a second after booting up.

Improving that length of time is a critical step in the quest to scale up from simple logic gates to larger computing systems.

The team’s code was able to drop error rates on IBM’s systems from 5.8% to 0.60%.

“One way to look at this is through the concept of entropy,” explains Flammia.

“All systems tend to disorder. In conventional computers, systems are refreshed easily, effectively dumping the entropy out of the system, allowing ordered computation.

“In quantum systems, effective reset methods to combat entropy are much harder to engineer. The codes we use are one way to dump this entropy from the system.”

Coding a Better Future

Coding, Ethics, Computer Science,All posts by antmilner

2019-02-28

Embedded EthiCS, a collaborative initiative between the Computer Science and Philosophy Departments, now offers a dozen courses, tripling its size since when it began spring 2017. The initiative, which offers interdisciplinary courses that address the ethical issues surrounding technology and computer science, also plans to expand to other disciplines.

We strongly applaud this exciting, innovative initiative from the Computer Science and Philosophy Departments. The creation of Embedded EthiCS affirms the two departments’ understanding that examining the ethics at play in a novel field like computer science is an essential part of developing the field responsibly. We are heartened by the program’s expansion, and further encourage the integration of this interdisciplinary approach in other academic departments so that ethics becomes a valued component of every discipline.

An understanding of ethical issues arising from the rapid growth of technology in our society is not only useful, but also morally vital. Issues of data collection and privacy of information — to name just a few concerns — have posed challenges in the field of computer science, and it is of the utmost importance that students concentrating in the field think seriously about them. To that end, the Embedded EthiCS program is not only creating new ethics-based courses, but also aiming at integrating ethical questions into pre-existing courses across Computer Science. By this process, rather than learning just the most efficient coding techniques, students will also have to confront the implications of the systems they create on the world around them.

At a place like Harvard, where students in all disciplines will go on to shape their fields, this type of interdisciplinary initiative should not be restricted to the Computer Science department. In light of ethical challenges emerging in other STEM fields like genetics, we feel that this initiative should expand to other schools across the University such as the School for Engineering and Applied Sciences. Encouragingly, the program already plans to expand to the Medical School. Even within the College, we hope that the program grows, so that all students, regardless of concentration, will be able to take ethical reasoning classes designed to engage directly with issues related to their concentration.

Even beyond Harvard, we encourage this type of interdisciplinary approach to learning at colleges and universities across the U.S. in all kinds of different contexts. By making the materials for Embedded EthiCS courses available online, the program has made concrete steps to work towards just such a goal. We commend this move, and hope these academic initiatives across Harvard and academia more broadly will encourage students to think more deeply about how they can use their talents not just to succeed in their industry of choice, but to build a better world.

This staff editorial solely represents the majority view of The Crimson Editorial Board. It is the product of discussions at regular Editorial Board meetings. In order to ensure the impartiality of our journalism, Crimson editors who choose to opine and vote at these meetings are not involved in the reporting of articles on similar topics.

The Cloud Is Just Someone Else's Computer

Cloud, Servers, CodingAll posts by antmilner

2019-02-28

When we started Discourse in 2013, our server requirements were high:

- 1GB RAM

- modern, fast dual core CPU

- speedy solid state drive with 20+ GB

I'm not talking about a cheapo shared cpanel server, either, I mean a dedicated virtual private server with those specifications.

We were OK with that, because we were building in Ruby for the next decade of the Internet. I predicted early on that the cost of renting a suitable VPS would drop to $5 per month, and courtesy of Digital Ocean that indeed happened in January 2018.

The cloud got cheaper, and faster. Not really a surprise, since the price of hardware trends to zero over time. But it's still the cloud, and that means it isn't exactly cheap. It is, after all, someone else's computer that you pay for the privilege of renting.

But wait … what if you could put your own computer "in the cloud"?

Wouldn't that be the best of both worlds? Reliable connectivity, plus a nice low monthly price for extremely fast hardware? If this sounds crazy, it shouldn't – Mac users have been doing this for years now.

A Gentle Introduction to Learning Curves for Diagnosing Machine Learning Model Performance

Machine Learning, AI, ML, Model PerformaceAll posts by antmilner

2019-02-28

A Gentle Introduction to Learning Curves for Diagnosing Machine Learning Model Performance

by Jason Brownlee on February 27, 2019 in Better Deep Learning

Tweet Share Share

A learning curve is a plot of model learning performance over experience or time.

Learning curves are a widely used diagnostic tool in machine learning for algorithms that learn from a training dataset incrementally. The model can be evaluated on the training dataset and on a hold out validation dataset after each update during training and plots of the measured performance can created to show learning curves.

Reviewing learning curves of models during training can be used to diagnose problems with learning, such as an underfit or overfit model, as well as whether the training and validation datasets are suitably representative.

In this post, you will discover learning curves and how they can be used to diagnose the learning and generalization behavior of machine learning models, with example plots showing common learning problems.

After reading this post, you will know:

- Learning curves are plots that show changes in learning performance over time in terms of experience.

- Learning curves of model performance on the train and validation datasets can be used to diagnose an underfit, overfit, or well-fit model.

- Learning curves of model performance can be used to diagnose whether the train or validation datasets are not relatively representative of the problem domain.

Let’s get started.

Overview

This tutorial is divided into three parts; they are:

- Learning Curves

- Diagnosing Model Behavior

- Diagnosing Unrepresentative Datasets

Learning Curves in Machine Learning

Generally, a learning curve is a plot that shows time or experience on the x-axis and learning or improvement on the y-axis.

Learning curves (LCs) are deemed effective tools for monitoring the performance of workers exposed to a new task. LCs provide a mathematical representation of the learning process that takes place as task repetition occurs.

— Learning curve models and applications: Literature review and research directions, 2011.

For example, if you were learning a musical instrument, your skill on the instrument could be evaluated and assigned a numerical score each week for one year. A plot of the scores over the 52 weeks is a learning curve and would show how your learning of the instrument has changed over time.

- Learning Curve: Line plot of learning (y-axis) over experience (x-axis).

Learning curves are widely used in machine learning for algorithms that learn (optimize their internal parameters) incrementally over time, such as deep learning neural networks.

The metric used to evaluate learning could be maximizing, meaning that better scores (larger numbers) indicate more learning. An example would be classification accuracy.

It is more common to use a score that is minimizing, such as loss or error whereby better scores (smaller numbers) indicate more learning and a value of 0.0 indicates that the training dataset was learned perfectly and no mistakes were made.

During the training of a machine learning model, the current state of the model at each step of the training algorithm can be evaluated. It can be evaluated on the training dataset to give an idea of how well the model is “learning.” It can also be evaluated on a hold-out validation dataset that is not part of the training dataset. Evaluation on the validation dataset gives an idea of how well the model is “generalizing.”

- Train Learning Curve: Learning curve calculated from the training dataset that gives an idea of how well the model is learning.

- Validation Learning Curve: Learning curve calculated from a hold-out validation dataset that gives an idea of how well the model is generalizing.

It is common to create dual learning curves for a machine learning model during training on both the training and validation datasets.

In some cases, it is also common to create learning curves for multiple metrics, such as in the case of classification predictive modeling problems, where the model may be optimized according to cross-entropy loss and model performance is evaluated using classification accuracy. In this case, two plots are created, one for the learning curves of each metric, and each plot can show two learning curves, one for each of the train and validation datasets.

- Optimization Learning Curves: Learning curves calculated on the metric by which the parameters of the model are being optimized, e.g. loss.

- Performance Learning Curves: Learning curves calculated on the metric by which the model will be evaluated and selected, e.g. accuracy.

Now that we are familiar with the use of learning curves in machine learning, let’s look at some common shapes observed in learning curve plots.

A Gentle Introduction to Learning Curves for Diagnosing Machine Learning Model Performance

by Jason Brownlee on February 27, 2019 in Better Deep Learning

Tweet Share Share

A learning curve is a plot of model learning performance over experience or time.

Learning curves are a widely used diagnostic tool in machine learning for algorithms that learn from a training dataset incrementally. The model can be evaluated on the training dataset and on a hold out validation dataset after each update during training and plots of the measured performance can created to show learning curves.

Reviewing learning curves of models during training can be used to diagnose problems with learning, such as an underfit or overfit model, as well as whether the training and validation datasets are suitably representative.

In this post, you will discover learning curves and how they can be used to diagnose the learning and generalization behavior of machine learning models, with example plots showing common learning problems.

After reading this post, you will know:

- Learning curves are plots that show changes in learning performance over time in terms of experience.

- Learning curves of model performance on the train and validation datasets can be used to diagnose an underfit, overfit, or well-fit model.

- Learning curves of model performance can be used to diagnose whether the train or validation datasets are not relatively representative of the problem domain.

Let’s get started.

A Gentle Introduction to Learning Curves for Diagnosing Deep Learning Model PerformancePhoto by Mike Sutherland, some rights reserved.

Overview

This tutorial is divided into three parts; they are:

- Learning Curves

- Diagnosing Model Behavior

- Diagnosing Unrepresentative Datasets

Learning Curves in Machine Learning

Generally, a learning curve is a plot that shows time or experience on the x-axis and learning or improvement on the y-axis.

Learning curves (LCs) are deemed effective tools for monitoring the performance of workers exposed to a new task. LCs provide a mathematical representation of the learning process that takes place as task repetition occurs.

— Learning curve models and applications: Literature review and research directions, 2011.

For example, if you were learning a musical instrument, your skill on the instrument could be evaluated and assigned a numerical score each week for one year. A plot of the scores over the 52 weeks is a learning curve and would show how your learning of the instrument has changed over time.

- Learning Curve: Line plot of learning (y-axis) over experience (x-axis).

Learning curves are widely used in machine learning for algorithms that learn (optimize their internal parameters) incrementally over time, such as deep learning neural networks.

The metric used to evaluate learning could be maximizing, meaning that better scores (larger numbers) indicate more learning. An example would be classification accuracy.

It is more common to use a score that is minimizing, such as loss or error whereby better scores (smaller numbers) indicate more learning and a value of 0.0 indicates that the training dataset was learned perfectly and no mistakes were made.

During the training of a machine learning model, the current state of the model at each step of the training algorithm can be evaluated. It can be evaluated on the training dataset to give an idea of how well the model is “learning.” It can also be evaluated on a hold-out validation dataset that is not part of the training dataset. Evaluation on the validation dataset gives an idea of how well the model is “generalizing.”

- Train Learning Curve: Learning curve calculated from the training dataset that gives an idea of how well the model is learning.

- Validation Learning Curve: Learning curve calculated from a hold-out validation dataset that gives an idea of how well the model is generalizing.

It is common to create dual learning curves for a machine learning model during training on both the training and validation datasets.

In some cases, it is also common to create learning curves for multiple metrics, such as in the case of classification predictive modeling problems, where the model may be optimized according to cross-entropy loss and model performance is evaluated using classification accuracy. In this case, two plots are created, one for the learning curves of each metric, and each plot can show two learning curves, one for each of the train and validation datasets.

- Optimization Learning Curves: Learning curves calculated on the metric by which the parameters of the model are being optimized, e.g. loss.

- Performance Learning Curves: Learning curves calculated on the metric by which the model will be evaluated and selected, e.g. accuracy.

Now that we are familiar with the use of learning curves in machine learning, let’s look at some common shapes observed in learning curve plots.

Want Better Results with Deep Learning?

Take my free 7-day email crash course now (with sample code).

Click to sign-up and also get a free PDF Ebook version of the course.

Download Your FREE Mini-Course

Diagnosing Model Behavior

The shape and dynamics of a learning curve can be used to diagnose the behavior of a machine learning model and in turn perhaps suggest at the type of configuration changes that may be made to improve learning and/or performance.

There are three common dynamics that you are likely to observe in learning curves; they are:

- Underfit.

- Overfit.

- Good Fit.

We will take a closer look at each with examples. The examples will assume that we are looking at a minimizing metric, meaning that smaller relative scores on the y-axis indicate more or better learning.

Underfit Learning Curves

Underfitting refers to a model that cannot learn the training dataset.

Underfitting occurs when the model is not able to obtain a sufficiently low error value on the training set.

— Page 111, Deep Learning, 2016.

An underfit model can be identified from the learning curve of the training loss only.

It may show a flat line or noisy values of relatively high loss, indicating that the model was unable to learn the training dataset at all.

An example of this is provided below and is common when the model does not have a suitable capacity for the complexity of the dataset.

Example of Training Learning Curve Showing An Underfit Model That Does Not Have Sufficient Capacity

An underfit model may also be identified by a training loss that is decreasing and continues to decrease at the end of the plot.

This indicates that the model is capable of further learning and possible further improvements and that the training process was halted prematurely.

Example of Training Learning Curve Showing an Underfit Model That Requires Further Training

A plot of learning curves shows overfitting if:

- The training loss remains flat regardless of training.

- The training loss continues to decrease until the end of training.

Overfit Learning Curves

Overfitting refers to a model that has learned the training dataset too well, including the statistical noise or random fluctuations in the training dataset.

… fitting a more flexible model requires estimating a greater number of parameters. These more complex models can lead to a phenomenon known as overfitting the data, which essentially means they follow the errors, or noise, too closely.

— Page 22, An Introduction to Statistical Learning: with Applications in R, 2013.

The problem with overfitting, is that the more specialized the model becomes to training data, the less well it is able to generalize to new data, resulting in an increase in generalization error. This increase in generalization error can be measured by the performance of the model on the validation dataset.

This is an example of overfitting the data, […]. It is an undesirable situation because the fit obtained will not yield accurate estimates of the response on new observations that were not part of the original training data set.

— Page 24, An Introduction to Statistical Learning: with Applications in R, 2013.

This often occurs if the model has more capacity than is required for the problem, and, in turn, too much flexibility. It can also occur if the model is trained for too long.

A plot of learning curves shows overfitting if:

- The plot of training loss continues to decrease with experience.

- The plot of validation loss decreases to a point and begins increasing again.

The inflection point in validation loss may be the point at which training could be halted as experience after that point shows the dynamics of overfitting.

The example plot below demonstrates a case of overfitting.

Example of Train and Validation Learning Curves Showing an Overfit Model

Good Fit Learning Curves

A good fit is the goal of the learning algorithm and exists between an overfit and underfit model.

A good fit is identified by a training and validation loss that decreases to a point of stability with a minimal gap between the two final loss values.

The loss of the model will almost always be lower on the training dataset than the validation dataset. This means that we should expect some gap between the train and validation loss learning curves. This gap is referred to as the “generalization gap.”

A plot of learning curves shows a good fit if:

- The plot of training loss decreases to a point of stability.

- The plot of validation loss decreases to a point of stability and has a small gap with the training loss.

Continued training of a good fit will likely lead to an overfit.

The example plot below demonstrates a case of a good fit.

Example of Train and Validation Learning Curves Showing a Good Fit

A Gentle Introduction to Learning Curves for Diagnosing Machine Learning Model Performance

Machine Learning, AI, ML, Model PerformaceAll posts by antmilner

2019-02-28

A Gentle Introduction to Learning Curves for Diagnosing Machine Learning Model Performance

by Jason Brownlee on February 27, 2019 in Better Deep Learning

Tweet Share Share

A learning curve is a plot of model learning performance over experience or time.

Learning curves are a widely used diagnostic tool in machine learning for algorithms that learn from a training dataset incrementally. The model can be evaluated on the training dataset and on a hold out validation dataset after each update during training and plots of the measured performance can created to show learning curves.

Reviewing learning curves of models during training can be used to diagnose problems with learning, such as an underfit or overfit model, as well as whether the training and validation datasets are suitably representative.

In this post, you will discover learning curves and how they can be used to diagnose the learning and generalization behavior of machine learning models, with example plots showing common learning problems.

After reading this post, you will know:

- Learning curves are plots that show changes in learning performance over time in terms of experience.

- Learning curves of model performance on the train and validation datasets can be used to diagnose an underfit, overfit, or well-fit model.

- Learning curves of model performance can be used to diagnose whether the train or validation datasets are not relatively representative of the problem domain.

Let’s get started.

Overview

This tutorial is divided into three parts; they are:

- Learning Curves

- Diagnosing Model Behavior

- Diagnosing Unrepresentative Datasets

Learning Curves in Machine Learning

Generally, a learning curve is a plot that shows time or experience on the x-axis and learning or improvement on the y-axis.

Learning curves (LCs) are deemed effective tools for monitoring the performance of workers exposed to a new task. LCs provide a mathematical representation of the learning process that takes place as task repetition occurs.

— Learning curve models and applications: Literature review and research directions, 2011.

For example, if you were learning a musical instrument, your skill on the instrument could be evaluated and assigned a numerical score each week for one year. A plot of the scores over the 52 weeks is a learning curve and would show how your learning of the instrument has changed over time.

- Learning Curve: Line plot of learning (y-axis) over experience (x-axis).

Learning curves are widely used in machine learning for algorithms that learn (optimize their internal parameters) incrementally over time, such as deep learning neural networks.

The metric used to evaluate learning could be maximizing, meaning that better scores (larger numbers) indicate more learning. An example would be classification accuracy.

It is more common to use a score that is minimizing, such as loss or error whereby better scores (smaller numbers) indicate more learning and a value of 0.0 indicates that the training dataset was learned perfectly and no mistakes were made.

During the training of a machine learning model, the current state of the model at each step of the training algorithm can be evaluated. It can be evaluated on the training dataset to give an idea of how well the model is “learning.” It can also be evaluated on a hold-out validation dataset that is not part of the training dataset. Evaluation on the validation dataset gives an idea of how well the model is “generalizing.”

- Train Learning Curve: Learning curve calculated from the training dataset that gives an idea of how well the model is learning.

- Validation Learning Curve: Learning curve calculated from a hold-out validation dataset that gives an idea of how well the model is generalizing.

It is common to create dual learning curves for a machine learning model during training on both the training and validation datasets.

In some cases, it is also common to create learning curves for multiple metrics, such as in the case of classification predictive modeling problems, where the model may be optimized according to cross-entropy loss and model performance is evaluated using classification accuracy. In this case, two plots are created, one for the learning curves of each metric, and each plot can show two learning curves, one for each of the train and validation datasets.

- Optimization Learning Curves: Learning curves calculated on the metric by which the parameters of the model are being optimized, e.g. loss.

- Performance Learning Curves: Learning curves calculated on the metric by which the model will be evaluated and selected, e.g. accuracy.

Now that we are familiar with the use of learning curves in machine learning, let’s look at some common shapes observed in learning curve plots.

A Gentle Introduction to Learning Curves for Diagnosing Machine Learning Model Performance

by Jason Brownlee on February 27, 2019 in Better Deep Learning

Tweet Share Share

A learning curve is a plot of model learning performance over experience or time.

Learning curves are a widely used diagnostic tool in machine learning for algorithms that learn from a training dataset incrementally. The model can be evaluated on the training dataset and on a hold out validation dataset after each update during training and plots of the measured performance can created to show learning curves.

Reviewing learning curves of models during training can be used to diagnose problems with learning, such as an underfit or overfit model, as well as whether the training and validation datasets are suitably representative.

In this post, you will discover learning curves and how they can be used to diagnose the learning and generalization behavior of machine learning models, with example plots showing common learning problems.

After reading this post, you will know:

- Learning curves are plots that show changes in learning performance over time in terms of experience.

- Learning curves of model performance on the train and validation datasets can be used to diagnose an underfit, overfit, or well-fit model.

- Learning curves of model performance can be used to diagnose whether the train or validation datasets are not relatively representative of the problem domain.

Let’s get started.

A Gentle Introduction to Learning Curves for Diagnosing Deep Learning Model PerformancePhoto by Mike Sutherland, some rights reserved.

Overview

This tutorial is divided into three parts; they are:

- Learning Curves

- Diagnosing Model Behavior

- Diagnosing Unrepresentative Datasets

Learning Curves in Machine Learning

Generally, a learning curve is a plot that shows time or experience on the x-axis and learning or improvement on the y-axis.

Learning curves (LCs) are deemed effective tools for monitoring the performance of workers exposed to a new task. LCs provide a mathematical representation of the learning process that takes place as task repetition occurs.

— Learning curve models and applications: Literature review and research directions, 2011.

For example, if you were learning a musical instrument, your skill on the instrument could be evaluated and assigned a numerical score each week for one year. A plot of the scores over the 52 weeks is a learning curve and would show how your learning of the instrument has changed over time.

- Learning Curve: Line plot of learning (y-axis) over experience (x-axis).

Learning curves are widely used in machine learning for algorithms that learn (optimize their internal parameters) incrementally over time, such as deep learning neural networks.

The metric used to evaluate learning could be maximizing, meaning that better scores (larger numbers) indicate more learning. An example would be classification accuracy.

It is more common to use a score that is minimizing, such as loss or error whereby better scores (smaller numbers) indicate more learning and a value of 0.0 indicates that the training dataset was learned perfectly and no mistakes were made.

During the training of a machine learning model, the current state of the model at each step of the training algorithm can be evaluated. It can be evaluated on the training dataset to give an idea of how well the model is “learning.” It can also be evaluated on a hold-out validation dataset that is not part of the training dataset. Evaluation on the validation dataset gives an idea of how well the model is “generalizing.”

- Train Learning Curve: Learning curve calculated from the training dataset that gives an idea of how well the model is learning.

- Validation Learning Curve: Learning curve calculated from a hold-out validation dataset that gives an idea of how well the model is generalizing.

It is common to create dual learning curves for a machine learning model during training on both the training and validation datasets.